The Fellows Journal is a forum for the current Library Publishing Coalition fellows to share their experiences and raise topics for discussion within the community. Learn more about the Fellowship Program.

Maybe it’s not all that surprising that I’ve come to think about ScholComm in terms similar to US politics. Right now, as I draft this blog post, we are just a handful of days away from the 2020 election and in January 2020, as the next (and hopefully different) president will be inaugurated, I will be compiling my tenure application. It’s been like this from the start. I was hired in February 2016, when the Republican Party presidential primaries were beginning, which was the same month I joined Twitter to better follow both politics and librarianship. Sometimes we get what we ask for.

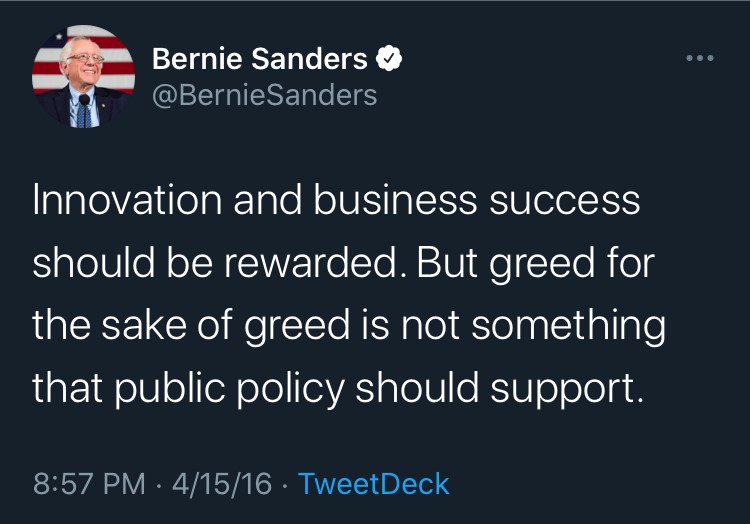

Twitter has been invaluable for keeping up with the latest ScholComm developments through conference live-tweets, article and policy announcements, and candid conversation between relevant figures in the field. I remember reading the first Plan S announcement tweet from cOAlition-S in 2018, and in fact the Library Publishing Coalition blipped onto my radar from #LPForum19 tweets. Using Twitter has also made me excruciatingly aware of the shape of our political fights, pushed me further leftward, and as I mentioned, caused me to think about ScholComm and politics through a similar framing. Here’s an example of how that can play out.

During the Vice Presidential debate, Sen. Kamala Harris said very clearly that Biden would not ban fracking if elected. It was not an inspiring moment, coming from someone who previously called for a fracking ban, but it was an understandable strategy. If you lose some swing-voters in Pennsylvania who possibly care about this issue, you risk losing the entire race to an administration whose policies on climate change are much worse than just allowing continued fracking.

But, if you do believe climate change to be an existential threat, why adopt a weakened stance on preventing it? I’ve thought this about private and public research funding agencies who champion open access. If you feel deeply about a cause, and it is within your power to make sweeping change, why keep on with the incremental?

I’m sure I’m being unfair in my stance. To capture a diverse constituency, a big-tent approach can be effective. Compromise can cause cynicism about our politics, but sometimes a little progress can be better than a lot of regression. That’s the story I’ve told myself, at least, while making my daily compromise as a ScholComm librarian who manages our Elsevier-owned institutional repository service, Digital Commons. My school contracted with bepress (then an independent company) shortly before hiring me to manage it, and my values felt fully aligned as I made the pitch across campus to deposit green OA manuscripts there. But that feeling changed with the announcement of Elsevier acquiring bepress in August 2017 (MacKenzie, 2017).

Since 2017, the Digital Commons service hasn’t worsened, but the premise that many customers initially bought into, of supporting an independent platform in the scholarly communication ecosystem, has eroded. And what do people do when they face a deterioration of goods and services? For A.O. Hirschman (1970), there are three choices (which later scholars have revised upon): exit, voice, and loyalty. In my case, exit seems out of the question: a diverse constituency of groups on my campus have now integrated the software, and a swap would be overly-costly and damage relationships in the process. I don’t know whether I’d categorize what I am doing now as voice or loyalty, but what I do know is that there is a strong glimmer of recognition when Sen. Harris walks her fracking-issue tightrope, or when grant-funding institutions rock the boat just lightly enough that it doesn’t risk a capsize.

Digital Commons still allows me to make works open access that were not previously, but I can still feel the ground shift under my feet. Remember the scene from There Will Be Blood when Daniel Day-Lewis humiliatingly shouts “I drink your milkshake!” to Paul Dano, revealing that he had drained Dano’s land dry of oil using wells located off-property. Well, it would seem that our milkshake (standing in for data [Oil!] about researcher activity) brings all the oligopolists to the yard, whether it’s buried in a transformative agreement or dredged from an IR or other education platform, refined, and sold back to the university (Aspesi & SPARC, 2018).

Vertical Integration

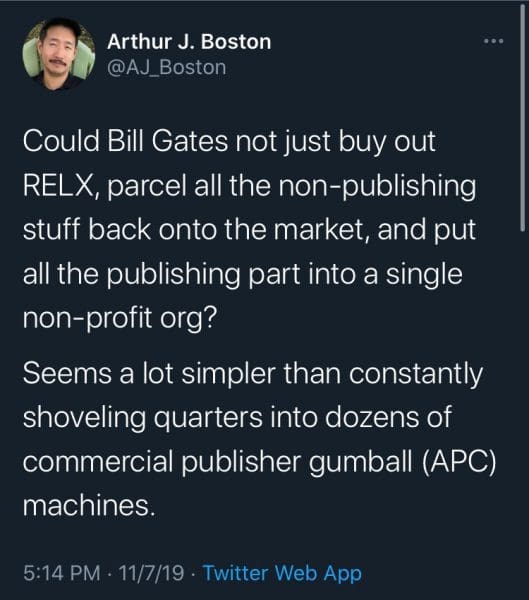

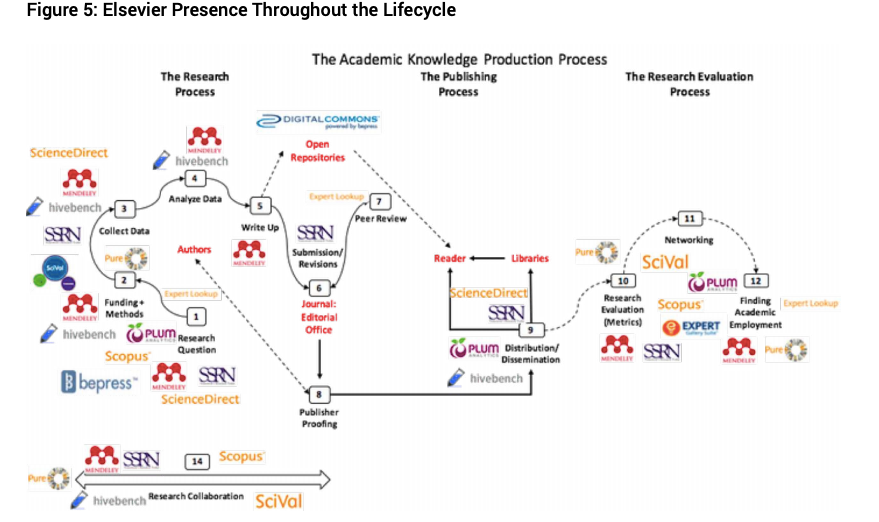

To be clear here, it’s not that I don’t understand that it costs money to run things or disagree that there is positive potential in using publishing data to gain insights. It’s that “scholarly communication is up for grabs,” and as Jefferson Pooley (2017) writes, it is unclear which camp will become the primary custodian of it: “the one profit-seeking” or “the other mission-committed” one. Pooley addressed the fates of the expanding scholarly architecture, with commercial acquisitions (Altmetric, figshare, Authorea, etc.) on one hand, and Mellon Foundation funded projects (Manifold, Open Library of Humanities, Hypothesis, etc.) on the other. And as Posada and Chen (2018) have documented, the five big commercial publishers have systematically been acquiring infrastructure that captures every stage of the academic knowledge production lifecycle.

At this point, it’s a fair question to ask: so what? One way to answer this question is to consider other industries where commercial enclosures are threatening independence. My home community has a lot of visible farm work that takes place, and with it, the “iconic image of the American farmer … who works the land, milks cows and is self-reliant enough to fix the tractor” as Laura Sydell (2015) of NPR described. When tractors break down, farmers have traditionally popped the hood and fixed problems as they arose in the field. But as tractors become increasingly outfitted with proprietary software, the only viable repair solution left becomes hauling into an authorized agent, suffering all the attendant costs and loss of time. The same for the crop being farmed, whose proprietary seeds (which cannot be saved year to year) are often used out of necessity for their resiliency to the proprietary insecticides used in the area.

Vertical integration throughout this supply chain marginalizes the ability of family farms to remain as independent operators, and thus, as diversifiers of market options. Scholar-led publications and infrastructure serve a similar function in our industry. It’s here that I’m reminded of the role of regulatory policy. In a 2019 Team Warren Medium post, Senator Elizabeth Warren condemned past policy decisions which favored increased corporate consolidation in the agriculture sector and cited her strong support for “a national right-to-repair law that empowers farmers to repair their equipment without going to an authorized agent.” As much as I admire Warren’s policy-making, I don’t hold my breath for a day any time soon when a top-down ruling will allow scholars to “get under the hood” and tinker with Digital Commons software to turn off the Elsevier data pipeline.

When Marcin Jakubowski confronted the tractor-repair issue on his own small farm, he said he realized that “the truly appropriate, low-cost tools” necessary for “a sustainable farm and settlement just didn’t exist yet.” In his 2011 Ted Talk, Jakubowski[1] said if he wanted “tools that were robust, modular, highly efficient and optimized, low-cost, made from local and recycled materials that would last a lifetime” rather than those “designed for obsolescence,” he would have to build them himself. Jakubowski works on a project called the Global Village Construction Set, which is a repository of open source plans for fifty machines his group has identified as the most important to modern life, including tractors.

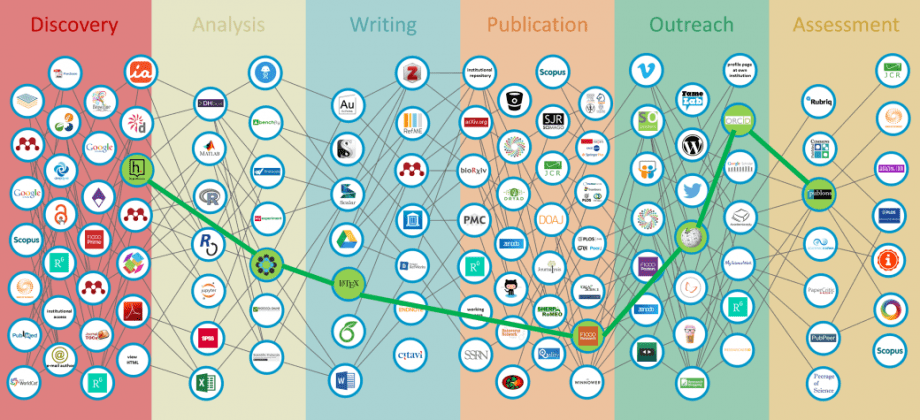

Luckily, the scholarly community has like-minded groups of people as this. Nate Angell summarized the 2018 Joint Roadmap for Open Science Tools workshop, where Bianca Kramer and Jeroen Bosman mapped out “an alternative open science workflow using open tools” through a thick continent of proprietary services.

For those of us considering ways to Exit, when Voice and Loyalty are no longer sensible options, how do we continue to foster and incentivize more work in open scholarly infrastructure? For those coders whose economic needs are being met by a higher education institution, we might expand the academy’s native system of recognition (citations!) to the work of maintainers, as others have proposed before. But what about entrepreneurs outside of employment in higher ed, with tools or ideas that may prove very useful to the academic community, for whom monetary remuneration will be the prime incentive? I want to conclude this post with an idea toward solving this final question.

A Proposal

Based on work by Nobel-winning economist Joseph Stiglitz, Senator Bernard Sanders proposed the Medical Innovation Prize Fund Act S1137 and S1138[1] in 2011 and 2017. One of the major outcomes from these bills, had they passed, would have been the creation of a prize fund, amounting to 0.55% of GDP ($80 billion in 2010). This pool of money would have funded cash prizes and an Open Source Dividend, paid out to developers of select healthcare treatments that chose to openly share access to the related knowledge, data, and technology, while denying themselves “the exclusive right to manufacture, distribute, sell, or use a drug, a biological product, or a medication manufacturing process.”[2]

What I am suggesting is that we find ways to do a version of this for scholarly infrastructure, to induce income-seeking developers of our favorite new research tools to release their code as open source, and to offer similar prizes on an annual basis to individuals (including the original developers) who release substantially updated versions, maintenance, and user support. Whether such a plan could have offered an incentive more lucrative than Elsevier’s offer to bepress is doubtful, but who knows?

David Lewis, et. al. (2018) proposed models in which every “academic library should commit to contribute 2.5% of its total budget to support the common infrastructure needed to create the open scholarly commons.” Since then, Invest In Open Infrastructure (investinopen.org) has taken the lead in organizing such an effort. Neylon offered the critique that 2.5% is both too ambitious of a target and not ambitious enough. For me, in 2020, considering the extreme financial difficulties that academic librarians have been driven to, exacerbated by this pandemic, I want to put a pin in the idea of asking more from them at all.

Instead, I wish to close out here with a different sort of proposal. A challenge, really. A challenge to the major commercial academic publishers—that we (the academy) fund—that claim to express a desire for a diverse marketplace and a thriving knowledge ecosystem. A challenge to the corporations that wish to rekindle good will. Lacking the power to tax you, I instead challenge you to devote 2.5% of your annual profit margin to fund open source, scholar-led infrastructures. In return for the free donation of your resources, you will receive the prestige and well-regard accorded to the association with the open-source projects such a fund could support.

Acknowledgement: Thanks to Kevin Hawkins for excellent feedback and recommendations. Any portions of this essay you disliked should be attributed to Kevin.

[1] https://www.ted.com/talks/marcin_jakubowski/transcript?language=en#t-5104

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prizes_as_an_alternative_to_patents#The_Medical_Innovation_Prize_Fund_Act_S1137_and_S1138

[3] https://www.congress.gov/bill/115th-congress/senate-bill/495/

Bibliography

Angell, N. (2018, September 13). 58 organizations gather to workshop a joint roadmap for open science tools. Joint Roadmap for Open Science Tools. https://jrost.org/2018/09/13/workshop.html

Aspesi, C., & SPARC. (2018). The academic publishing industry in 2018. SPARC: Community Owned Infrastructure. https://infrastructure.sparcopen.org/landscape-analysis/the-academic-publishing-industry-in-2018

Hirschman, A. O. (1970). Exit, voice, and loyalty: Responses to decline in firms, organizations, and states. Harvard University Press.

Jakubowski, M. (2011, March). Transcript of “Open-sourced blueprints for civilization.” TED. https://www.ted.com/talks/marcin_jakubowski_open_sourced_blueprints_for_civilization/transcript

Lewis, D. W., Goetsch, L., Graves, D., & Roy, M. (2018). Funding community controlled open infrastructure for scholarly communication: The 2.5% commitment initiative. College & Research Libraries News, 79(3), 133. https://doi.org/10.5860/crln.79.3.133

McKenzie, L. (2017, August 3). Elsevier makes move into institutional repositories with acquisition of Bepress. Inside Higher Ed. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2017/08/03/elsevier-makes-move-institutional-repositories-acquisition-bepress

Neylon, C. (2018, January 5). Against the 2.5% Commitment. Science In The Open. https://cameronneylon.net/blog/against-the-2-5-commitment/

Pooley, J. (2017, August 15). Scholarly communications shouldn’t just be open, but non-profit too. LSE Impact Blog. https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/impactofsocialsciences/2017/08/15/scholarly-communications-shouldnt-just-be-open-but-non-profit-too/

Posada, A., & Chen, G. (2018). Inequality in knowledge production: The integration of academic infrastructure by big publishers. In L. Chan & P. Mounier (Eds.), ELPUB 2018. https://doi.org/10.4000/proceedings.elpub.2018.30

Sydell, L. (2015, August 17). Diy tractor repair runs afoul of copyright law. All Tech Considered. https://www.npr.org/sections/alltechconsidered/2015/08/17/432601480/diy-tractor-repair-runs-afoul-of-copyright-law

Team Warren. (2019, March 27). Leveling the playing field for america’s family farmers. Medium. https://medium.com/@teamwarren/leveling-the-playing-field-for-americas-family-farmers-823d1994f067